Jane Addams by Louise W. Knight

Author:Louise W. Knight

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

Published: 2010-03-14T16:00:00+00:00

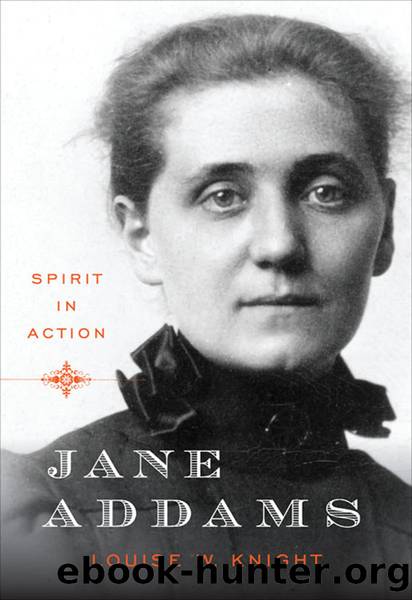

Jane Addams in 1910

Many conservatives found her views troubling, if not horrifying, but others respected and listened to her. Her friend in the Womenâs Trade Union League Margaret Dreier Robins noticed. She told her, âIn all America I know of only one person who can reach the honorable conservatives of this country and rouse from them a rallying cry and that is you.â In a 1910 editorial, on the occasion of Addams being named an honorary member of the Chicago Association of Commerce, the Chicago Tribune noted that while conservatives had once foolishly considered her âan anarchistâ or âa dangerous meddler,â most people now understood âthe enlightened conservatism of her viewsâ¦and [her] work[.]â28

Why had she become such a popular figure? Certainly her ideas had appeal. People were drawn to her vision of a generous-spirited, inclusive, more socially and politically democratic United States. And there was also the fame-generating nature of two of her main occupations of speaking and writing. Since 1889 she had been steadily and increasingly in the public eyeâlecturing, recycling her speeches in a wide variety of publications, writing her own books. Finally there was the appeal of her personality.

People attending a lecture remembered her understated but compelling presence. They recollected her âearnestness,â her âeager voice,â and her âdeep eyes.â29 Her niece, Aliceâs daughter Marcet, wrote, âShe made no effort to be oratoricalâ¦yetâ¦from the first word to the last she held the complete attention of her audience.â30 One resident thought she was the âfinest impromptu speakerâ he had ever heard.31 Addams stood with her hands behind her and spoke in a natural tone of voice. Because of her elocution training at Rockford, everyone, even those in large audiences, could hear her (without a microphone, of course).

Then there was the way she made her arguments. She did not accuse, characterize, or judge. She interpreted. Although she supplied facts and endorsed principles, she often focused on matters of the heartânot on sentimentality, for which she had an aversion, but on âspiritualâ matters, as she liked to refer to them: the human feelings of responsibility, compassion, and affection; the human longings for freedom, meaning, and connection. There was something magical about the way she could pry open closed minds and let lightâin the form of empathyâflood in.

Her radical form of goodness needed labeling and containing. The popular stereotype of a âgood womanââa saintâcame readily to mind. An Atlanta journalist struck the obvious note, writing in 1907, âIn the hearts of thousands of Americans, high and low, Miss Addams justly ranks as Saint Jane.â32 Her friend John Burns, the British labor organizer, declared her âthe first saint America had produced.â33 One newspaper reporter compared her with Joan of Arc. Another quoted a professor who had said: âShe has attained the heavenly beauty of the Madonna[,] for she has borne the suffering of the people.â34 Kind, inclusive, interested in the âspiritualâ side of human relations, she certainly fitted the female version of a saint better than did, say, the impatient Florence Kelley. It also helped that she was an upper-middle-class woman who worked among âthe poor.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Civilization & Culture | Expeditions & Discoveries |

| Jewish | Maritime History & Piracy |

| Religious | Slavery & Emancipation |

| Women in History |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32554)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31951)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31935)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19067)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14376)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13323)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12022)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5368)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5217)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5093)

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari(4911)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4775)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(4591)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(4528)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4473)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4209)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4107)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(4093)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3963)